memcache internals

Tagged with: [ memcache ]

Memcache is a pretty well-known system inside the web-community and for a good reason. It’s fast, flexible, lightweight and it looks like installing memcache on your servers automatically increases your website speed tenfold or more. Ok, so that’s a bit over the top, but still: having a good caching-strategy in place can help your website/application. If you want to know how to implement memcache in your website you’re out of luck. This post isn’t about starting with memcache. We are going to pop the trunk and see what’s under the hood.. What exactly makes memcache so magical??

Even though memcache on itself is not a very complex piece of software, it’s got lots of nifty features which would take too long to talk about. I’ll focus on 4 of them:

- Big-O

- LRU

- Memory allocation

- Consistent hashing

Big-O

Most of memcache functionality (add, get, set, flush etc) are o(1). This means they are constant time functions. It does

not matter how many items there are inside the cache, the functions will take just as long as they would with just 1

item inside the cache. For more information about big-o, please read this blogpost that does a bit of explaining. Having O(1) functions has a lot of advantages

(memcache is and STAYS fast), but also some drawbacks. For instance: you cannot iterate over all your items inside

memcache (if you need to do that, you are seriously misusing memcache, but that is another subject I suppose). An

iterator would probably be a O(N) operation, which means the amount of time doubles when the amount of items in the

cache doubles. This is the main reason that memcache does not support that kind of functionality.

LRU algorithm

Before you start a memcache-daemon, you have to tell it how much memory it should use. It will allocate that memory right from the start so if you want to use 1GB of data for memcache storage, that 1GB memory is allocated directly and cannot be used for other purposes (like for apache or a database for instance). But because we tell memcache how much memory it can use, it might be possible that we fill the whole memcache memory with our data. What would happen when we need to add even more?

As you might already know, memcache will delete old data to make room for your new data, but it needs to know which data-object can be deleted. Is it the largest one so we instantly have a lot of room? Or maybe it’s the first one entered, so you get a FIFO based caching system? Turns out, memcache uses a much more advanced technique called LRU: Least Recently Used. In a nutshell: it deletes the item that isn’t used for the longest period of time. This doesn’t have to be the largest object though. And it even doesn’t have to be the first object stored in the cache.

Internally, all objects have a “counter”. This counter holds a timestamp. Every time a new object is created, that counter will be set to the current time. When an object gets FETCHED, it will reset that counter to the current time as well. As soon as memcache needs to “evict” an object to make room for newer objects, it will find the lowest counter. That is the object that isn’t fetched or is fetched the longest time ago (and probably isn’t needed that much, otherwise the counter would be closed to the current timestamp).

In effect this creates a simple system that uses the cache very efficient. If it isn’t used, it’s kicked out of the system.

Adam Presley has written a nice blogpost to show you how such a system would be implemented in PHP. In memcache, the system that is used works a bit differently, all to make sure that most memcache functionality stays o(1).

Memory allocation

Memory allocation is an area that lies outside the reach for most php developers. That’s why programming in higher level language is so easy: most of the work is done by the underlying systems like the compilers and operating systems. But since memcache is written in C, it has to do its own memory allocation and management. Luckily, most of that work can (and must) be delegated to the operating system so in fact, we only have to deal with a function that allocates memory (malloc), a function that frees up some memory in case we don’t need it anymore (free), and maybe a function that can resize a current memory block (realloc).

Now, this is all fine when you are creating a (simple) application in C, where you need to allocate some memory to create a string, do some things with it, and in the end, free up the memory that has been used. But high performance systems like memcache can get into trouble working that way. The reason is that malloc() and free() functions are not really optimized for such kind of programs. Memory gets fragmented easily which means a lot of memory will get spilled, just like you can spill a lot of diskspace when you write/delete a lot of files on your filesystem (but in all fairness, this depends on the filesystem you use). Do you remember the time that you had to defragment your disks regulary? Basically the same thing still can happen in your memory and it means memory allocation would become slow and a lot of memory will be unused at the end due to this fragmentation.

Now, in order to combat this “malloc()” problem, memcache does its own memory management by default (you can let memcache use the standard malloc() function, but that would not be advisable). Memcache’s memory manager will allocate the maximum amount of memory from the operating system that you have set (for instance, 64Mb, but probably more) through one malloc() call. From that point on, it will use its own memory manager system called the slab allocator.

Slab allocation

When memcache starts, it partitions its allocated memory into smaller parts called pages. Each page is 1Mb large (coincidentally, the maximum size that an object can have you can store in memcache). Each of those pages can be assigned to a slab-class, or can be unassigned (being a free page). A slab-class decides how large the objects can be that are stored inside that particular page. Each page that is designated to a particular slab-class will be divided into smaller parts called chunks. The chunks in each slab have the same size so there cannot be 2 different sized chunks inside the same page. For instance, there could be a page with 64byte chunks (slab class 1), a page with 128byte chunks (slab class 2) and so on, until we get the largest slab with only 1 chunk (the 1MB chunk). There can be multiple pages for each slab-class, but as soon as a page is assigned a slab-class (and thus, split up in chunks), it cannot be changed to another slab-class.

The smallest chunk-size starts at 80 bytes and increases with a factor of 1.25 (rounded up until the next power of 2). So the second smallest chunksize would be 100 etc. You can actually find it out by issuing the “-vv” flag when starting memcache. You can also set the factor (-f) and the initial chunk-size (-s), but unless you really know what you are doing, don’t change the initial values.

$ memcached -vv slab class 1: chunk size 80 perslab 13107 slab class 2: chunk size 100 perslab 10485 slab class 3: chunk size 128 perslab 8192 slab class 4: chunk size 160 perslab 6553 slab class 5: chunk size 200 perslab 5242 slab class 6: chunk size 252 perslab 4161 slab class 7: chunk size 316 perslab 3318 slab class 8: chunk size 396 perslab 2647 slab class 9: chunk size 496 perslab 2114

You actually see the slab class numbers, the chunk size inside the slab and how many chunks there are (the higher the chunk-size, the lower the number of chunks obviously). Memcache will initially create 1 page per slab-class and the rest of the pages will be free (which even slab class needs a page, gets a page) Now that memcache has partitioned the memory, it can add data to the slabs. Suppose I have a data object of 105 bytes (this includes the overhead from memcache, so what you would store inside memcache is actually a bit less). Memcache would know it should use a chunk in the slab-3 class since it’s the first class where the 105-byte object would fit. This also means that we have a penalty of 128-105 = 23 bytes that are unused. There is NO WAY that memory can be used for something else. That chunk is marked as used and that’s it. It’s the penalty we get from using the slab allocator but it also means our memory doesn’t get fragmented. In fact, it’s all a speed/memory waste trade-off.

Now, as soon as a complete page if full (all chunks in the page are filled) and we need to add another piece of data, it will fetch a new free page, assign it to the specified slab-class, partition it into chunks and gets the first available chunk to store the data. But as soon as there are no more pages left that we can designate to our slab-class, it will use the LRU-algorithm to evict one of the existing chunks to make room. This means that when we need a 128byte chunk, it will evict a 128byte chunk, even though there might be a 256byte chunk that is even older. Each slab-class has its own LRU.

So hypothetical:

If you fill your whole cache with 128-byte chunked data (slab class 3 in our case), it will assign all free pages to that slab-class. There would be in effect be only 1 (initial) page for each other slab-class, which means that when you have an object that needs to be stored in the 1MB page, a second 1MB object cannot allocate a new page. Therefore, memcache must use the LRU to remove an object, and since there can only be one object in the 1-MB slab-class, that object is removed. If you get the last paragraph, you understand how the slab-allocator works :)

Consistent hashing

Your web application can talk to multiple memcache-servers at the same time. You only need to update your application with a list of ip’s where your memcache servers are located so it automatically use all your servers.

As soon we add an object to the memcache, it will automatically choose a server where it can store the data. When you have only one server that decision is easy, but as soon as you have multiple servers running it must find a way to place items. Lots of different algorithms can be used for this. For instance: a round-robin system that will store each object onto the next server on every save-action (1st object saved into server 1, 2nd object into server 2, 3rd object into server 1, etc etc). But how would such a system know the correct server when we want to fetch the specified data?

What memcache normally does is a simple, yet very effective loadbalance trick: for each key that gets stored or fetched, it will create a hash (you might see it as md5(key), but in fact, it’s a more specialized - quicker - hash method). Now, the hashes we create are pretty much evenly distributed, so we can use a modulus function to find out which server to store the object to:

In php’ish code, it would do something like this:

$server_id = hashfunc($key) % $servercount;

That’s great. Now we can deduce which server holds the specified key just by this simple formula. The trouble with this system: as soon as $servercount (the number of servers) change, almost 100% of all keys will change server as well. Maybe some keys will get the same server id, but that would be coincidence. In effect, when you change your memcache server count (either up or down, doesn’t matter), you get a big stampede on your backend system since all keys are all invalidated at once.

Now, let’s meet consistent hashing. With this algorithm, we do not have to worry (much) about keys changing servers when your server count goes up or down. Here’s how it works:

Consistent hashing uses a counter that acts like a clock. Once it reaches the “12”, it wraps around to “1” again. Suppose this counter is 16 bits. This means it ranges from 0 to 65535. If we visualize this on a clock, the number 0 and 65535 would be on the “12”, 32200 would be around 6’o clock, 48000 on 9 o’clock and so on. We call this clock the continuum.

On this continuum, we place a (relative) large amount of “dots” for each server. These are placed randomly so we have a clock with a lot of dots.

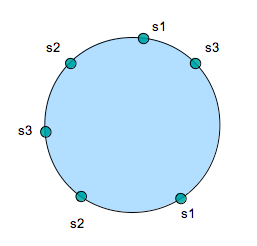

As an example, let’s display a continuum with 3 servers (s1, s2 and s3) and 2 dots per server:

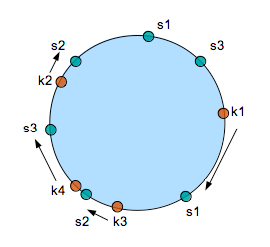

If the continuum is a 16 bit number, dots for s1 are around 10 and 29000, more or less. s2 would have dots on 39000 and 55000, and s3 would have 8000 and 48000. Now, when we store a key, we can create a hash that result in a 16 bit number. That number can be plotted onto the continuum as well. We have 4 keys (k1 to k4) which result into 4 numbers: 15000, 52000, 34000, and 38000. Visualized as the red dots in the next figure (pardon my drawing-skills):

To find the actual server where a key should be stored, the only thing we need to do is follow the continuum clock until we hit a “server”-dot. For k1 we follow the continuum until we hit server s1. K2 will hit dot s2. K3 will hit s2, and k4 will hit s3. So far, there is nothing really special happening. In fact, it looks like a lot of extra work to achieve something we could easily do with our modulus-algorithm.

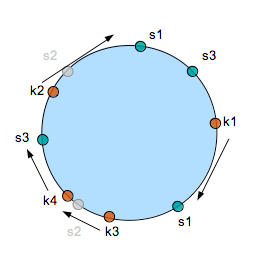

Here is where consistent hashing is advantageous: Suppose server 2 will be removed from the memcache server pool. What would happen when we want to fetch key k1? Nothing strange would happen. We plot k1 still on the same position in the continuum, and the first server-dot it will hit is still s1.

However, when fetching k3, which is stored on s2, it would miss the s2-dot (since it has been removed), and will be moved to server s3. Same goes for k2, which moves from s2 to s1.

In fact, the more server-dots we place onto the continuum, the less key-misses we get in case a server gets removed (or added). A good number would be around 100 to 200 dots, since more dots would result in a slower lookup on the continuum (this has to be a very fast process of course). The more servers you add, the better the consistent hashing will perform.

Instead of almost 100% of the key-movements you have when using a standard modulus algorithm, the consistent hashing algorithm would maybe invalidate 10-25% of your keys (these numbers drop down quickly the more servers you use) which means the pressure on your backend system (like the database) will be much less than it would when using modulus.

More reading

- http://www.mikeperham.com/2009/01/14/consistent-hashing-in-memcache-client/

- https://github.com/memcached/memcached

- http://code.google.com/p/memcached/wiki/FAQ

- http://code.google.com/p/memcached/wiki/NewUserInternals

Conclusion

It’s nice to take a deeper look at some systems we take for granted. As in “real life”, things are much more complicated and consists of many sophisticated ways of solving problems that, in fact, might help you in your own (development) life. Algorithms like LRU and consistent hashing aren’t that hard to grasp and just the fact that you know now they exist, can help you become a better developer in the long run.